Am I the only one cognizant of this golden anniversary? I hope not. Recorded at Plaza Studios in New York City on April 22, 1963 Boss Guitar is more than enjoyable: it is essential Wes Montgomery. (I'm merely contradicting Scott Yanow's opinion, as excerpted in the Wiki article on the album.) The sensibility of his later albums (Boss Guitar was his ninth) provides the session's "popular" atmosphere, but it is drenched in the mind-engaging improvisational chops the world had already heard on The Incredible Jazz Guitar of Wes Montgomery and other LPs.

I recommend to jazz guitarists reading this that they "live" with each of Wes's solos for a concentrated period (if they have not already done so), immerse themselves in these gems of spontaneous musical composition, intently notice how he builds them, "dig" the signature earthy texture with which his calloused right thumb incarnated their every note. They are as emotionally accessible to the casual listener as they are challenging to the veteran player.

It's a trio date -- the recently deceased Mel Rhyne on Hammond B-3, the apparently immortal Jimmy Cobb on drums -- that packs the punch of a big band. If you feel you must sample what I'm talking about before acquiring this CD, I am pleased to note that the tracks are available on YouTube, but I'm embedding it here for your convenience:

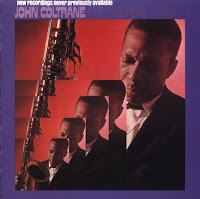

Not seven weeks earlier, the eponymously titled, and classic, collaboration of John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman, which we have celebrated, to mention no other great contemporaneous jazz recording, had transpired. 1963 was memorable for transition (Pope John XXIII dies mid-Vatican Council on June 3, Paul VI is elected), trail-blazing (the March on Washington on August 28th, but also many other sentinel events in the history of the civil rights movement), and tragedy (JFK's assassination, subsequent/consequent escalation of US involvement in Vietnam).

But it was also the year the Beatles made pop culture history with Please, Please Me and Meet the Beatles. Comic book superheroes Iron Man and the X-Men continue to do that, but those superheroes debuted fifty years ago. James Bond's second cinematic adventure, From Russia with Love, hit the big screen.

That year Blue Note Records released Blues for Lou, Am I Blue, and Idle Moments all three albums helmed by its most prolific musician, Grant Green. But as wonderful as they are, and as much as they continue to delight, Boss Guitar must be singled out for the extraordinary gifts it bestows. And as infrequently as I tend this blog, I could not proceed with anything else today without saying so.