In 1954, February 21st fell on a Sunday.

In that morning’s New York Times you might have been amused by a little article on Atlantic City boardwalk chairs by Gay Talese. (He was then working as a copy boy at the Times.)

By 1954, you probably owned a black-and-white television. In April, RCA would launch its first color model. If you stayed home that evening, you could have seen Lucille Ball play mystery guest on What’s My Line?, which had premiered on CBS only a few weeks earlier. Or you could have bought a ticket to see her surprise hit comedy, The Long, Long Trailer, which had opened a few days earlier.

If you were au courant, you knew the war against polio would accelerate that Tuesday in Pittsburgh, where children would be vaccinated en masse, thanks to Dr. Jonas Salk and his colleagues. And, as in our time, Egypt was in the news with Gamal Abdel Nasser’s grabbing the helm of state two days later.

The same week What’s My Line? hit the airwaves, President Eisenhower used them to warn against American intervention in Vietnam—after authorizing $385 million to fight communists there (on top of the $400 million already committed).

To put those millions in perspective: gas was 29 cents a gallon; a loaf of bread, 17 cents; a stamp, 3. The average working stiff grossed $4,700 a year, putting that thousand-dollar color TV out of reach for most.

BUT . . .

If you loved jazz, then for the cost of a few drinks you could have witnessed heaven on earth at Birdland, Hard Bop’s Bethlehem, “The Jazz Corner of the World.” For an equivalent amount today, you can download the tracks that Alfred Lion produced and Rudy Van Gelder so expertly recorded there that night, which practically put you at a table down in that Broadway & 52nd Street basement. (Yes, you can find heaven in a basement.)

For February 21, 1954 was the night The Art Blakey Quintet (or, "Art Blakey and His All Stars," as Birdland's M.C. Pee Wee Marquette announced) recorded what became A Night at Birdland, Volumes 1 and 2 (Blue Note 1521 and 1522).

VOLUME 1

1. Split Kick (Silver)

2. Once In A While (Green-Edwards)

3. Quicksilver (Silver)

4. Wee-Dot (Johnson-Parker)

5. Blues (Traditional)

6. A Night In Tunisia (Gillespie-Paparelli)

7. Mayreh (Silver)

VOLUME 2

1. Wee-Dot (Johnson-Parker)

2. If I Had You (Shapiro-Campbell)

3. Quicksilver (Silver)

4. The Way You Look Tonight (Kern-Fields)

5. Lou's Blues (Donaldson)

6. Now's The Time (Parker)

7. Confirmation (Parker)

In his distinctive delivery, the M.C. appeals to the audience's vanity: their applause will be part of the recording session and then announces the line-up:

". . . the great Art Blakey, and his wonderful group, the new trumpet sensation, Clifford Brown, Horace Silver on piano, Lou Donaldson on alto, Curly Russell on bass."

Marquette does not announce them as "The Jazz Messengers," even though Blakey had used "Messengers" on and off for the title of his various groups since 1947 (e.g., "The Seventeen Messengers," reflecting Blakey's conversion to Islam). The album covers refer simply to "Art Blakey Quintet." They become "The Jazz Messengers" regularly after Hank Mobley joins the group later that year, and "Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers" permanently after co-leader Horace Silver leaves in 1958.

(Stephen Schwartz and Michael Fitzgerald's virtually complete discography of Blakey and his ensembles is enhanced by many excerpts from interviews with him, so I encourage you to explore their site.)

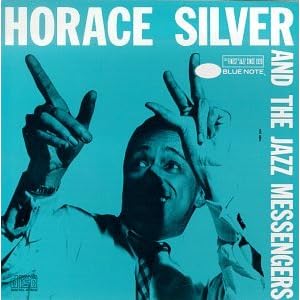

In the interest of accuracy, we should remember the joint leadership of Blakey and Silver who (unlike Blakey) contributed many songs to the band's book. Indeed, in 1955 the group was known as "Horace Silver and the Jazz Messengers," and it recorded under that very name.

Some of the stand-out tunes: "Split Kick" (a contrafact of Harry Warren's "There Will Never Be Another You"); two versions of Michael Edwards' "Once in a While"; two of Horace Silver's breakneck "Quicksilver" (which recalls, and rivals in inventiveness, Bird's most distinctive compositions); Dizzy Gillespie's "A Night in Tunisia" that could make me forget Blakey's 1960 studio version featuring Lee Morgan, Wayne Shorter, Bobby Timmons, and Jymie Merritt. (I am ashamed to admit that I have not yet encountered the recording of the 1957 line-up that tackled that classic: Jackie McLean, Johnny Griffin, Bill Hardman, Sam Dockery, and Spanky DeBrest. Both albums are titled, A Night in Tunisia.)

Two versions of a J. J. Johnson' and Leo Parker's fast blues, "Wee Dot," surround "Mayreh," another Silver bebopper. The featuring of two of Charlie Parker's signature tunes, "Confirmation" and "Now's the Time," nearly a decade after they heralded the birth of bop, shows Bird's continuing influence over the next generation.

The longest track (10:15) belongs to Jerome Kern's "The Way You Look Tonight," Oscar winner for Best Original Song (Fred Astaire crooned it to Ginger Rogers in Swing Time in 1936). It is exemplary of how the jazz improviser can mine and refine hitherto undiscovered harmonic and melodic possibilities of popular music. In his solo Lou Donaldson (born 1926), throws in the proverbial kitchen sink, including a taste of Rimsky-Korsakov's "Flight of the Bumblebee" (just as his idol Bird, on that very stage three years earlier, interpolated the opening of Igor Stravinsky's Firebird Suite, to its composer's delight, into his solo on "Ko-Ko").

After finishing "Now's the Time" (vol. 2, track 3), Blakey with his crisp, resonant voice, acknowledges to his audience

"that I'm working now, and I hope forever, with the greatest musicians in the country today. That includes Horace Silver, Curly Russell, Lou Donaldson, and Clifford Brown. Let's give them a big round of applause! Yes sir, I'm gonna stay with the youngsters, and when these get too old I'm gonna get some younger ones. Keeps the mind active."

Of this stellar outfit, only Donaldson and Silver (born 1928) are still with us. (When I was being introduced to jazz in the early '70s, these two gentlemen had taken their music in a direction that didn't interest me, and so their improvisational and compositional gifts on so many historic recordings stayed below my radar for too many years. May no one reading this make that mistake.) A car accident took Brownie's life in June of 1956, and Blakey himself passed away in 1990. Bebop bass pioneer Dillon "Curly" Russell (1917-1986) had left music altogether by 1960. (Miles Davis' bop classic "Donna Lee" was named after his daughter.)

Hard bop expert Eric B. Olsen (who compiled the discography for Silver's autobiography Let's Get to the Nitty Gritty) does not list A Night at Birdland in his list of 100 Hard Bop albums which he lists chronologically. If he had, that session -- one of the first "live" recordings of jazz -- would have been listed third. Perhaps that's because while the players are all budding hard boppers, the music they made that night is bebop. There's no hint of gospel or rhythm & blues, elements that set that stage of jazz's evolution off from its predecessor. Listen to two other double-album sets by Blakey and the Messengers recorded six years later in the same club: At the Jazz Corner of the World and Meet You at the Jazz Corner of the World. It's Bebop-Plus.

No, A Night at Birdland isn't hard bop. But anyone, 57 years ago tonight, who wanted to see and hear its progenitors would have had to skip What's My Line? and make their way to Broadway & 52nd. A lucky few did, and as Pee Wee Marquette promised, their applause was immortalized on wax along with the searing sonorities they cheered.