61 years ago, December 15, 1949, a basement club -- following (I'm not sure of the order) the Ubangi, the Ebony, and The Clique -- opened as Birdland: The Jazz Corner of the World. Its birth coincided with the demise of "The Street," i.e., the serendipitous concatenation of jazz clubs that sprung up on 52nd Street between Fifth and Seventh Avenues in the wake of Prohibition. (For a complete history, see Patrick Burke's scholarly Come In and Hear the Truth: Jazz and Race on 52nd Street. Arnold Shaw's 52nd Street: The Street of Jazz makes an excellent companion reader.)

A daytime shot of legendary 52nd Street -- on its last legs in the late '40s.

The upscale jazz club and restaurant on Manhattan's West 44th Street possessing legal title to "Birdland" is therefore not topic of this post. (On its home page, take the "History" link to a fact-filled page about its historic predecessor.) With all due respect to that venue for the great music and food it offers, it is not the historic Birdland that was effectively the House of Hard Bop from its first stirrings in the early '50s to its ripening in the early '60s.

The address is 1674 Broadway, at the corner of 52nd Street . . .

A view of NE corner of Broadway & 52nd Street

. . . but Birdland had its own number, 1678 (probably to expedite delivery of the great volume of mail it must have received compared to that of other tenants), as can be seen on this flyer from 1955, every detail of which is worth savoring:

Above, left pane: Broadway looking north, fans line up for Sarah Vaughn;

right pane: looking south.

Below: This is what awaited them:

right pane: looking south.

Below: This is what awaited them:

Above, right pane: George Shearing's "Lullaby of Birdland," the club's theme song is noted.

Below: cover of contemporary sheet music for "Lullaby of Birdland."

Above: notable guests included: Duke Ellington, Dean Martin, Jerry Lewis, Sammy Davis, Jr., Marlon Brando, . . . and Harry Belafonte, who helped open Birdland on December 15, 1949. Just a sampling of the stars who regarded Birdland as the place to see and be seen -- and hear - great jazz. Yet nothing marks the spot.

The cover of Birdland's menu:Below: cover of contemporary sheet music for "Lullaby of Birdland."

Above: notable guests included: Duke Ellington, Dean Martin, Jerry Lewis, Sammy Davis, Jr., Marlon Brando, . . . and Harry Belafonte, who helped open Birdland on December 15, 1949. Just a sampling of the stars who regarded Birdland as the place to see and be seen -- and hear - great jazz. Yet nothing marks the spot.

For the first few weeks of its existence, Birdland's guests were greeted by birds in cages suspended from the ceiling. They were a nice touch, but the poor things could not survive the combination of smoke and air-conditioning.

The current occupant of that basement is Flash Dancers (part of its awning is visible, next to Leone's Pizza Pasta) -- of which I will say no more:

Here's a daytime shot, 1960, by William Caxton:

Clearly the inspiration for the cover art for Birdland Stars 1956:

At All About Jazz, Bertil Holmgren sketches a portrait of Birdland as he experienced it one night in June 1962, when the John Coltrane Quartet was "on duty":

A rather small club, maybe 150 square meters, after descending down the stairs from 52nd Street [that makes no sense to me; but in our exchange of comments, Mr. Holgren stood by his memory], which is a side street to Broadway at Times Square [Birdland was situated in the Times Square area, but Times Square, where the New York Times was once published, like Longacre Square before it, was ten blocks south of Birdland], the room opened up with the bandstand right in front and with a bar along the left wall.Behold, the left wall (that's Jay McNeely on tenor sax):

[Holgren continues:] To the right, on the opposite side from the bar, as well as just in front of it, there were rows of chairs reserved for listeners only, and in the middle a number of tables, maybe ten to fifteen, were placed where certain solid and liquid nourishments could be taken.Behold, the right wall: Erroll Garner and Art Tatum

On stage: Bud Powell, Miles Davis, Lee Konitz, Art Blakey

Bird with Strings, 1951

[Holgren continues:] On the tables were nothing but white-and-red-chequered cloths and black plastic ashtrays carrying the words “Birdland - The Jazz Corner of the World” in white. . . .

[Holgren continues:] Since the drinking age limit was 21, how I, younger than that, managed entrance belongs to the secrets you learn when you are desperate to gain admission! Initially I would be sitting as far from the bar as possible (an imperative requirement by the door guard), but eventually I would slowly move forward and by the time Trane started set no. 2, I'd have him one meter in front of me, the McCoy [Tyner] piano to the left, [Jimmy] Garrison to the right and a steam boiler called Elvin [Jones] further back. This felt to me a bit like being in the middle of the engine room on The Titanic . . . . I believe they started playing at around 9:00 P.M., in forty-five minute sets interrupted by half hour intermissions, and the place closed at 5:00 A.M.

The roster for opening night is worth a study in itself:

For ninety-eight cents -- "including tax" -- one could have the history of jazz parade before one's ears "from Dixieland to Bop." Imagine Charlie Parker, Lennie Tristano, and Lester Young on the same stage! (Is that Max Kaminsky and Kenny Dorham on trumpets in the photo below? And who's the fellow looking at the camera? Where is he now?)

The "Roy Haines" listed on the poster is, of course, Roy Haynes, still going strong at 85. He played the new Birdland on the original's 60th anniversary last year (and was there again last week)!

On August 25, 1959, on the Broadway sidewalk just outside Birdland, Miles Davis was beaten and arrested by police for insisting that they misapprehended his chivalry. As the Wikipedia article on Miles summarizes the altercation:

After finishing a 27-minute recording for the armed service, Davis took a break outside the club. As he was escorting an attractive blonde woman across the sidewalk to a taxi, Davis was told by Patrolman Gerald Kilduff to "move on." Davis explained that he worked at the nightclub and refused to move. The officer said that he would arrest Davis and grabbed him as Davis protected himself. Witnesses said that Kilduff punched Davis in the stomach with his nightstick without provocation. Two nearby detectives held the crowd back as a third detective, Don Rolker, approached Davis from behind and beat him about the head. Davis was then arrested and taken to jail where he was charged with feloniously assaulting an officer. He was then taken to St. Clary Hospital where he received five stitches for a wound on his head.

Davis attempted to pursue the case in the courts, before eventually dropping the proceedings in a plea bargain in order to recover his suspended Cabaret Card, enabling him to return to work in New York clubs. [End of Wikipedia account.]

More details are provided on this blog post on last year's anniversary of the beating.

A while back, with this event on my mind, meandering near that spot, I was startled by a billboard-size advertising of VH-1's Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Awards. The huge poster hung on the north wall of the Sheraton Manhattan Hotel, just south of 1674 Broadway. Startled, because as though looking down on the spot where he was humiliated, across the street and across half a century, was the triumphant visage of Miles himself, a Hall inductee. I could not interest any passerby in this irony.

A collection of albums subtitled "Live at Birdland" would fill a shelf. Chronologically, this is probably the first:

Miles Davis' from 1951:

Here's "Lullaby of Birdland" composer George Shearing's from '52:

Bill Evans, 1960:

But this pair of 1954 albums (Volume 1 and Volume 2) turned Birdland into the Bethlehem of Hard Bop (which is, after all, what we're mainly about here):

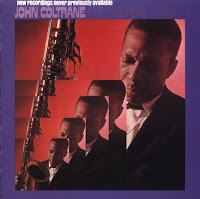

I almost left out this classic from 1963!

Birdland still pleasantly haunts the memories of thousands of musicians and their fans. Their numbers dwindle daily, however, and the few who do remember seem to wish not to be bothered about it.

(One exception is Nat Hentoff who, during a phone chat, confirmed its location for me and related his brief encounter with Bird himself [once banned from the club named after him for want of a cabaret license] on the stairs between the club and a street-level eatery, which was probably where Leone's pizza parlor is.)

For sixteen years the greatest music in the world was generated nightly within its walls until it succumbed to the accounting ledger logic that doomed The Street a generation earlier. Birdland deserves its historian. May those of us who can offer oral testimony, artifacts, and other evidence be ready when he or she makes inquiry.

In the meantime, if you wish to share your knowledge about or memories of Birdland on this blog, by all means, do so!